11

Aug 2019

17

Aug 2017

Trump Revokes Obama Order Protecting Infrastructure Projects from Climate Impacts

Dr. Franco Montalto, President and Principal Engineer at eDesign Dynamics, was quoted in this article in NPR's State Impact regarding Trump's decision to rescind Obama order requiring federal projects to consider climate change. Written by Susan Phillips.

President Trump has rolled back rules aimed at protecting federal infrastructure projects from rising sea levels and dangerous storms caused by climate change. Trump announced the move on Tuesday, at a press conference touting plans to fast track the building of roads and bridges.

Just before engaging in a hostile exchange with reporters over the violence in Charlottesville, President Trump said the current environmental rules governing construction of federal infrastructure projects created delays and costs.

“This overregulated permitting process is a massive, self-inflicted wound on our country,” Trump said standing at a podium in Trump Tower in New York City. “It’s disgraceful. Denying our people much needed investments in their community.”

Referring to a highway he wouldn’t name, getting built in a state he wouldn’t name, Trump said his executive order would reduce both costs and the timeline of the unknown project.

“It costs hundreds of millions of dollars, but it took 17 years to get it approved and many, many, many, many pages of environmental impact studies,” he said holding up a long piece of paper that appeared to have the approval process mapped out and then shifting to a shorter piece of paper. “This is what we will bring it down to. This is less than two years.”

As part of his broad executive order on infrastructure, Trump revoked an executive order put in place by President Obama in 2015 that bolstered protections for federally funded projects like roads and bridges, from the impact of climate change related flooding.

One group that supports Trump’s move is the National Association of Home Builders.

“NAHB commends President Trump for signing this executive order that rescinds the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard (FFRMS), an overreaching environmental rule that needlessly hurt housing affordability,” said NAHB Chairman Granger MacDonald in a statement. “The FFRMS posed unanswered regulatory questions that would force developers to halt projects and raise the cost of housing. This action by President Trump will provide much-needed regulatory relief for the housing community and help American home buyers.”

But environmentalists, planners and climate researchers criticized the move as short-sighted and dangerous.

Franco Montalto is an environmental engineering professor and climate researcher at Drexel University. He is also North American director of the Urban Climate Change Research Network.

“It would be a shame if local governments would have to choose between accepting federal dollars, which allows them to build infrastructure in the first place,” he said, “and accepting those dollars but not building what the scientific community would tell you is a prudent choice.”

Montalto says saving money on the front end could mean having to spend more later when the infrastructure is damaged by floods caused by rising seas or increased storms, like another Hurricane Sandy.

“According to a NOAA report originally published in 2013, and revisited and statistically reconfirmed in 2015, there has been an increasing trend in “billion dollar disasters” in the United States,” said Montalto, “of which more than half of total losses are due to floods, severe storms, or tropical cyclones.”

Coastal communities across the country, including Philadelphia, are already working to shore up existing infrastructure in the face of rising seas and potentially destructive storms like Hurricane Sandy.

“While it is true that climate-proofing infrastructure can be more costly than the cost of building the same infrastructure without considering future climate, it is also true that efforts to reduce climate risks now will reduce the need for disaster relief and recovery,” he said.

A spokesman for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers said it’s too early to tell how Trump’s new executive order will impact current and future projects.

Christine Knapp, Philadelphia’s Office of Sustainability director says regardless of the President’s executive order, the city will continue to consider the impact of sea level rise on its infrastructure projects.

See the original article >>HERE<<

21

Mar 2017

Science of the Living City Forum

Originally published by Earthdesk

Dr. Franco Montalto, Principal Engineer at eDesign Dynamics, collaboratively organized the "Science of the Living City" forum, February 21st.

Municipalities across the country are wrestling with overburdened urban infrastructure where, during wet weather events (i.e., rain and snow melt), combined sewer overflows (CSOs) introduce untreated sewage into local waterways, a violation of state and federal water policy. On February 21st, Pace University’s Dyson College Institute for Sustainability and the Environment partnered with the New York City Urban Field Station (a partnership between the US Forest Service, NYC Parks, and the Natural Areas Conservancy) to host a Science of the Living City seminar on how to leverage green stormwater infrastructure (i.e., green infrastructure) investments to both meet regulatory requirements for clean water and enhance urban sustainability and resilience. Living City

Panel participants Franco Montalto, Andrea Parker, Christina Rosan, Marit Larson, John McLaughlin, Michael Finewood, and Sara Meerow came from diverse professional experiences, including universities, government agencies, and nonprofits, and have overlapping interests in the multiple benefits—or multifunctionality—of green infrastructure. Our discussion broadened the conversation about the diverse challenges and benefits of incorporating green infrastructure into sustainable city planning.

Municipalities are facing enormous costs related to repairing and upgrading water systems. Citing potentially lower costs and multiple community benefits, stakeholders have strategized to implement green infrastructure as a stormwater management tool. Green infrastructure is defined here as technologies that mimic biologic systems to control water at the source, such as rain gardens, bioswales, and green roofs. NYC is a national leader in this regard, proposing to manage 10% of impervious surface with green infrastructure (learn more about the NYC GI Program here).

The evening opened with a presentation of Meerow’s research developing a Green Infrastructure Spatial Planning (GISP) model for identifying priority areas across New York City (as well as Detroit) where the multiple social and environmental benefits of green infrastructure are needed most. The panel then addressed critical questions about working in the diverse communities where green infrastructure is often sited. We learned a couple of key things from our conversation. For example, we can see how different organizations can share the same goal (e.g., clean water) but have distinct mandates for both how to achieve it and what the best outcomes are. Nonprofits may want green infrastructure that meets specific community needs while municipalities have to focus on stormwater runoff.

Likewise, both within and between communities, desires and needs are diverse. It can be challenging to meet them with technologies like green infrastructure. A nonprofit or government agency’s internal culture or politics may even constrain innovative or transformative action. An additional issue is timeframes. In other words, communities often want long-term engagement and planning, but municipalities and private firms are often under tighter deadlines.

The point is that green infrastructure is not a silver bullet for solving multiple problems at once; it offers many opportunities to provide co-benefits. But implementing green infrastructure is complicated. There must be engagement between all constituencies and we should adapt as our knowledge evolves.

A key point that emerged from our conversation was the necessity for public/private partnerships. Municipalities can implement green infrastructure on public property across cities (indeed, they often do), but that may not be sufficient to meet stormwater regulations. In this view, private property owners must play a role in meeting this common good. There were several open questions about these public/private partnerships, such as: How do we incentivize private property owners? How do we avoid inequities that can result from a focus on private property (see, for example, Heynen et al 2006)? How do we ensure that these infrastructures are maintained properly over time? To address these concerns, panelists emphasized the importance of community engagement, education, and stewardship as necessary parts of sustainability planning.

Importantly, our conversation demonstrated that we are all interested in meeting the multiple challenges that stormwater presents and we share a strong desire to contribute to sustainable communities. It is clear that we want an equitable, resilient, and sustainable future established through innovation in planning, community engagement, and public/private partnerships. And the challenges go beyond just local needs. Across the world, cities are growing and, as Montalto pointed out, we cannot design them like we always have and expect a different outcome. In this view, cities like NYC can be a model for global cities in meeting stormwater challenges.

Authors Michael Finewood and Samantha Miller are part of Pace University’s Dyson College Institute for Sustainability and the Environment (DCISE) Michael Finewood is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Environmental Studies and Science and Samantha Miller is Program Manager for DCISE.

The Science of the Living City event was organized collaboratively by Renae Reynolds (NYC Urban Field Station), Ruth A. Rae (NYC Parks), Bram Gunther (NYC Parks), Franco A. Montalto (Drexel University), Andrea Parker (Gowanus Canal Conservancy), Christina Rosan (Temple University), Marit Larson (NYC Parks), John McLaughlin (NYC Environmental Protection), and Sara Meerow (University of Michigan/ASU). Living City

3

Jan 2017

THE UNITED NATIONS CLIMATE CONFERENCE

![]()

About the Writer:

Franco Montalto

Dr. Montalto, PE is a licensed civil/environmental engineer and hydrologist with 20 years of experience working in urban and urbanizing ecosystems as both a designer and researcher. His experience includes planning, design, implementation, and analysis of various natural area restoration and green infrastructure projects.

![]()

About the Writer:

Hugh Johnson

Hugh has consulted on various aspects of renewable energy and energy efficiency for private, municipal, and federal clients. At Drexel, he contributes technical expertise and manages special projects.

Resolving to Act After the 2016 U.S. Election and the United Nations Climate Conference

The following article was originally created and posted on The Nature of Cities website. The full article may be read here: >>CLICK<<

Franco Montalto, Philadelphia and Venice. Hugh Johnson, Philadelphia.

January 2, 2017

We attended the 22nd session of the United Nations Climate Conference (also called COP22) as “Observers” in the immediate aftermath of the U.S. 2016 presidential election. Since 1995, the COP has served as the annual UN climate conference, providing an opportunity to assess progress, negotiate agreements, and disseminate information regarding global climate change action. This year’s COP was simultaneously exhilarating and uplifting, a message that we are determined to bring home to a country still reeling from an election that has elevated someone who called climate change a hoax to our nation’s highest office.

At COP22, even the recent election of Donald Trump could not quash the sense of momentum building around widespread action on climate change.

Thanks to its official Observer status, our employer, Drexel University, was one of hundreds of civil society institutions from around the world permitted to send a delegation to the two-week meeting in Marrakech, Morocco (7-18 November 2016). Our Office of International Programs and our Institute for Energy and the Environment sent an envoy of 10 faculty and students to this meeting, five each week. Our role as “observers” was none other than to attend the various summits, official meetings, and side events and to report on the actions that nation-states, indigenous peoples, businesses, mayors, and individuals are taking to address the challenges posed by climate change. We networked with other civil-service institutions, conducted an informal survey, listened to talks, and were interviewed by National Public Radio (11/21/16, State Impact NPR, “Pennsylvania Academics Find Inspiration at Climate Conference”).

The ongoing actions being discussed in Morocco would not have been possible if not for the historic agreement reached last year in Paris at COP21. The so-called “Paris Agreement” represented the first time that world leaders achieved global consensus regarding the need to work collaboratively to hold future global temperature increases to under 2 degrees Celsius. Over the last year, national governments had to formally ratify the agreement. Only 55 countries, accounting for 55 percent of global greenhouse gas (or GHG) emissions, needed to formally ratify the historic agreement for it to go into force; however, according to U.S. Secretary of State, John Kerry, speaking at the meeting in Marrakech, more than 109 countries—collectively responsible for 75 percent of global GHGs—had already signed prior to COP22, a much faster pace of ratification than anyone expected. Clearly, the need for global climate action has become a widely-held international value, shared not just by scientists and environmentalists, but also by governmental leaders, their rank and file governing bodies and agencies, and the private sector, whose interests underlie many political decisions.

With the signed agreement in force, conversations in the restricted Blue Zone of this year’s COP, focused on implementation strategies, identifying knowledge gaps, networking, and financing. The various meetings highlighted the efforts that individual countries have undertaken to identify the sources of their existing emissions, and gave them a platform to articulate their specific strategies for achieving their nationally determined contributions (or NDCs) to global GHG emission reductions. Discussions also addressed how specific countries, cities, and other sub-national actors are planning to nurture, manage, or shape forecasted economic and population growth, peacekeeping, and advances in human rights while keeping their emissions under control. Again according to Secretary Kerry, each nation is now in the process of developing its own plan, tailored to its own circumstances, and according to its own abilities. It is an example of common but “differentiated responsibilities”, with the most vulnerable nations being helped along by those most equipped to address this challenge.

In the publicly-accessible Green Zone of the meeting, attendees were largely focused on the role that the private sector and civil society can and must play. In small and large booths, vivid displays highlighted everything from the voluntary emission reduction goals of large multi-national corporations to small-scale entrepreneurial efforts to innovate new ways of deriving fuel from waste, or to create new market opportunities for existing technologies such as the “Nigerian Refrigerator,” which can cool a pot of fruit from 40°C to 4°C relying solely on evaporative processes. The Green Zone included interactive meetings where individuals could spontaneously join group discussions focusing on climate justice, racism, and other struggles intimately related to climate change. It also featured an international, socially-engaged art exhibit.

Marrakech, a beautiful city situated at the foot of the Atlas Mountains and at the edge of the Sahara Desert, was the perfect backdrop for this kind of multi-faceted exchange of ideas. Each day, as our group walked through its central square, the Jemaa el-Fna, a dynamic urban space packed with storytellers and snake charmers, musicians and dancers, traders and merchants, street food vendors, and children, we thought, what better setting to host the growing cross-cultural, global dialogue regarding the planet’s future? The square’s air is full of smoke, smells, sounds, and slang; its perimeter is lined with shops, rooftop restaurants, and street-level cafés. A vibrant, multi-actor, pulsating center of contrasts between old and new, of negotiation and of barter, it represents, in miniature, what is now happening on the world stage between global leaders, policymakers, entrepreneurs, and other vested individuals.

But what was most exhilarating to witness was how integrated the global response to climate change has become inside other contemporary efforts to improve the human condition. COP22 is just the most recent of a historic string of new pacts and agreements that will collectively guide the next phase of global human development. It began in 2015, when the United Nations officially replaced its Millennium Development Goals (or MDGs) with 17 Sustainable Development Goals (or SDGs), and 169 carefully articulated and intimately-related targets. The SDGs point the way to the next wave of progress on poverty alleviation, environmental protection, and the spreading of economic prosperity. A few months later, in March 2015, and at the request of the UN General Assembly, the Sendai Agreement for Disaster Risk Reduction—another global pact focusing on resilience and reducing the impacts of disasters on lives, livelihoods, health, and economic, physical, social, cultural and environmental assets—was adopted. The Paris Agreement was signed on December 12, 2015, and went into effect less than one year later on 5 October 2016. On October 15, 2016, after the conclusion of all-night negotiations in Kigali, Rwanda, an agreement was reached to limit the use of hydrofluorocarbons (or HFCs) resulting in the largest potential temperature reduction ever achieved by a single agreement, as much as 0.5 C. Later in October of 2016, in Quito, Ecuador, the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (called Habitat III) concluded with the adoption of the New Urban Agenda, a document that establishes new global standards for sustainable urban development, focusing on the collaborations necessary to more sustainably build, manage, and live in cities.

The “conversation” in Marrakech focused on how policymakers, planners, designers, business leaders, and individuals from all corners of the globe can integrate all of these different goals and aspirations into actionable initiatives at local, regional, national, and international scales. How can we design safe, accessible cities, with low-carbon transport systems, stable governing bodies, and equitable access to resources? How can we re-imagine our coastlines as multifunctional living landscapes, equipped to adapt to rising sea levels, but also supportive of critical fisheries, emergent habitats, and other forms of biodiversity? Where and how, in geographical and economic terms, will we feed ourselves, live, earn a living, and play, as both the global and urban populations of the world reach historical proportions? What successful models have been piloted, and what can we learn from them? These and other related, intellectually stimulating, and fundamentally important questions were on the lips of just about everyone we bumped shoulders with on the sprawling conference grounds.

Personally, we were reassured to witness this important conversation elaborated in so many different ways, by so many different people, in so many different languages, at COP22, even as the U.S. prepares for a new president. President-elect Donald Trump’s dismissive rhetoric during the campaign, and the expressed views of many individuals he appears poised to appoint as part of his Cabinet, suggest that this administration may not instinctively understand the urgency of global collaboration on any of these issues. Where the Obama administration has lead, the incoming administration seems, at least initially, to want to close the door. Like many other Americans attending the meeting, we used phrases like “angrily charged” and “disillusioned, but determined” to describe our post-election feelings at a workshop organized at the conference by Mediators Without Borders (or MWB) as an outlet for attendees to express our emotional reactions to the election results, and to convert these into a constructive reorientation of our professional activities.

To elicit global perspectives on the election, our Week Two delegation designed an informal survey to conduct after the MWB workshop, as we circulated among the tens of thousands of conference attendees. It featured two core questions: “What was your reaction when you heard the results of the U.S. election?” and, “Do you have a message for the incoming U.S. Administration regarding climate change?” Though we would be remiss not to mention that among the conference attendees were certainly a small group individuals who were unsurprised, or even satisfied, by Mr. Trump’s victory, responses to the first question overwhelmingly reflected many of the same feelings of shock, horror, and devastation articulated in the MWB workshop. But regardless of their feelings about Mr. Trump, and without exception, respondents to the second survey question urged the President Elect to follow his predecessor’s example by collaborating with the international community on efforts to battle climate change and to also lead in related struggles for sustainable development.

Leaders from all levels of government have expressed the same sentiment, tinged with optimism that significant backpeddling may no longer be tenable. UN Secretary General Ban ki-Moon said he counts “on the U.S.’s continued engagement and leadership to make this world better for all…” Brian Deese, Senior Climate Advisor to President Obama, reported in Marrakech that for the first time in human history, carbon emissions are now completely decoupled from economic growth. And Jonathan Pershing, the U.S. Special Envoy on Climate Change, stated confidently that, “The transition to clean energy is now inevitable.” While we still have many profound challenges, “the momentum is insurmountable: there is no stopping,” he said. Indeed, the recent open letters from more than 300 companies and from 37 red band blue state mayors asking President-Elect Trump not to abandon the Paris Agreement is further evidence of the deep roots that this movement now has.

This month, Drexel became the North American Hub of the Urban Climate Change Research Network. We have listed two preliminary goals to guide our activities: we will continue to generate and to disseminate scientific knowledge where it can inform sound decisions and policy, and to support our practitioner colleagues in their efforts to implement change. But in other contexts—ones where change must be catalyzed through other means—we are prepared to apply other forms of pressure, drawing from the enormous fountain of energy, creativity, and connections available to us through the growing international demand for climate action, social justice and sustainability. We invite you to join us as we transition from debates to determined action at all levels of our global community.

Franco Montalto and Hugh Johnson

Philadelphia

23

Dec 2016

The First Smart Sponge City Forum

Eric Rothstein, Managing Partner and Engineer at eDesign Dynamics, attended "The First Smart Sponge City Forum & The Launching of the Research Center for Sponge City, Wuhan University," December 17-19 in Wuhan, China.

Eric Rothstein was a keynote and the title of the talk was 'Innovations in Green Infrastructure Design and Monitoring in New York City." He was flown in as the New York expert to share his experience in design and monitoring of green infrastructure in New York City.

So what is a smart sponge city?

Instead of funneling rainwater away, a sponge city retains it for use within its own boundaries. Some might be used to recharge depleted aquifers or irrigate gardens and urban farms. Some could replace the drinking water we use to flush our toilets and clean our homes. It could even be processed to make it clean enough to drink.

China has enthusiastically embraced the idea of sponge cities because few countries are wrestling so painfully with the twin problems of rapid urbanisation and poor water management. Around half of China's cities are considered water scarce or severely water scarce by UN measures, and another half fail to reach national standards for flood prevention.

China has now chosen 16 urban districts across the country, including Wuhan, Chongqing and Xiamen, to become pilot sponge cities. Over the next three years, each will receive up to 600m yuan to develop ponds, filtration pools and wetlands, as well as to build permeable roads and public spaces that enable stormwater to soak into the ground. Ultimately, the plan is to manage 60% of rainwater falling in the cities.

A smart sponge city follows the philosophy of innovation: that a city can solve water problems instead of creating them. In the long run, sponge cities will reduce carbon emissions and help fight climate change.

21

Nov 2016

NPR Interviews Dr. Franco Montalto at Climate Conference

Dr. Franco Montalto, Principal Engineer at eDesign Dynamics, attended the twenty-second session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 22) held in Bab Ighli, Marrakech, Morocco from 7-18 November 2016.

The Conference successfully demonstrated to the world that the implementation of the Paris Agreement is underway and the constructive spirit of multilateral cooperation on climate change continues.

Please read the NPR interview below.

NPR Interview:

Pennsylvania Academics Find Inspiration at Climate Conference

The climate change conference in Morrocco ended over the weekend with an urgent message to president-elect Donald Trump – join the battle against global warming or risk contributing to catastrophe and moral failure. About 25,000 people attended the gathering aimed at keeping the earth from over-heating, and staving off the impacts like rising seas, droughts and increasingly destructive storms.

When Moravian College professor Diane Husic woke up the morning after election day in Marrakech, she headed to the United Nations climate change conference with a cloud over her head.

“We came in and it didn’t matter what country you were from,” said Husic, “this place was just in a fog. And everyone was coming up to us and saying, ‘did you vote for Donald Trump and what is that going to mean for us?’ I think most of us on Wednesday were in shock and didn’t know what to say.”

Husic is a veteran of these climate change conferences, she’s been bringing students here since 2009.

But she never expected that a man who called climate change a “Chinese hoax” and vowed to pull the U.S. out of the landmark climate agreement etched out in Paris last year, would be leading the country.

But like everyone at the U.N. climate conference in Morrocco, Husic says she quickly switched gears. And is returning home to Pennsylvania energized to act on reducing carbon emissions and improving things in the Bethlehem area.

“I think a lot of the change is going to be driven at the local level,” said Husic. “I know in the Lehigh Valley, there’s a lot of groups getting together because flooding is a big problem. It’s the Delaware watershed that we share with Philadelphia. So I think separate of who is in the governor’s office or who is in the White House, a lot of the work is going to be done on the local level.”

There’s a legitimate fear now, that if the U.S., which contributes 20 percent of the global carbon emissions, withdraws from the Paris Agreement, the entire global accord could fall apart.

The U.S. is also one of the wealthiest nations, and as such, has pledged money to help poor nations adapt. If that money dries up, other countries could follow suit.

Husic’s friend Franco Montalto is a professor at Drexel University, and he runs an organization dedicated to helping cities adapt to climate change.

“My message would be, stay calm, stay clear headed, focus on what needs to be done,” said Montalto. “Put your energy into making sure the next elections and the mid-terms, focus on your local elections, making sure you are supporting folks who will really lead into the way we need to be led, not what we’ve been hearing is going to come out of the new administration.”

Sitting under a tent drinking tea in the Moroccan desert, Husic, Montalto and a group of students and professors from eastern Pennsylvania all said they were encouraged by the conference, especially after going through such a divisive election season back home.

“You’ve got 197 countries here all with different priorities and urgencies and yet they can come together, and work not only on getting the Paris Agreement, but now implementing it,” said Husic. “I walked in this morning and saw all the flags displayed and I thought, unity. And I guess that’s the message I’m going back to, that we’re all in this together.”

All the countries attending the conference pledged to continue no matter what Donald Trump decides to do. But they all left Morocco staring into the unknown. The new administration takes power in just a couple of months. And so far, there has been no word from them regarding climate change.

Susan Phillips reported from Morocco on a fellowship from the International Reporting Project (IRP).

This NPR interview was originally published online at >>NPR.org<<

17

Nov 2016

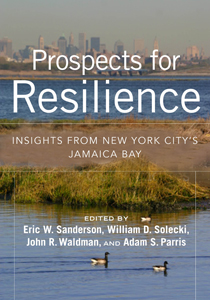

Book Release: Prospects for Resilience

Dr. Franco Montalto, Principal Engineer here at eDesign Dynamics, co-authored a chapter

in the new book Prospects for Resilience: Insights from New York City's Jamaica Bay.

|

Given the realities of climate change and sea-level rise, coastal cities around the world are struggling with questions of resilience.

Resilience, at its core, is about desirable states of the urban social-ecological system and understanding how to sustain those states in an uncertain and tumultuous future. How do physical conditions, ecological processes, social objectives, human politics, and history shape the prospects for resilience? Most books set out “the answer.” This book sets out a process of grappling with holistic resilience from multiple perspectives, drawing on the insights and experiences of more than fifty scholars and practitioners working together to make Jamaica Bay in New York City an example for the world.

Prospects for Resilience establishes a framework for understanding resilience practice in urban watersheds. Using Jamaica Bay—the largest contiguous natural area in New York, home to millions of New Yorkers, and a hub of global air travel with John F. Kennedy International Airport—the authors demonstrate how various components of social-ecological systems interact, ranging from climatic factors to plant populations to human demographics. They also highlight essential tools for creating resilient watersheds, including monitoring and identifying system indicators; computer modeling; green infrastructure; and decision science methods. Finally, they look at the role and importance of a “boundary organization” like the new Science and Resilience Institute at Jamaica Bay in coordinating and facilitating resilience work, and consider significant research questions and prospects for the future of urban watersheds.

Prospects for Resilience sets forth an essential foundation of information and advice for researchers, urban planners, students and others who need to create more resilient cities that work with, not against, nature.

17

Oct 2016

Build Landscapes – Biannual Event in Turin, Italy

Franco Montalto, PE, PhD, recently presented some of eDesign Dynamics' recent work at a biannual event organized by the Fondazione per l'Architettura di Torino in Turin, Italy.

This year's event took place between the 13th and 16th of October, and was called Creare Paesaggi (Build Landscapes).

In his invited contribution, Dr. Montalto talked about multifunctional parks and other urban landscapes. He also showcased projects designed by EDD, and monitored by his research group at Drexel.

URBAN PARKS was the theme of the Biennale Create Landscapes 2016The urban park project is a key environmental renewal, urban and social tool through which you can rehabilitate degraded areas of the city and take action with respect to environmental hazards.It also has the ability to affect the quality of life of citizens, providing them with open spaces in response to social and cultural questions.Within metropolitan cities it is vital to ensure the environmental and recreational functions of the green, in the form of parks, it plays a very important role in spatial planning.In light of these considerations, one wonders, during the Biennale, how to implement and manage systems supra green spaces, with what new features you have to equip them and what new parameters should be developed to insert the green between services for the metropolitan population.

10

Jul 2016

Professor Montalto’s Sustainable Water Resource Engineering Class in Venice

From June 8-18, 2016, CAEE Professor Dr. Franco Montalto, P.E. brought a group of 13 student to Venice, Italy as part of his Sustainable Water Resource Engineering class.

The theme of this year's class was Water and Jobs, the name also given to the 2016 World Water Development Report produced by World Water Assessment Program (WWAP). Since it is estimated that 3 out of 4 global jobs are water dependent, new approaches to water management can help to foster new forms of sustainable development. The group explored this theme with a focus on historical and contemporary water management strategies in Venice, a city of water.

After an introductory presentation by Dr. Angela Ortigara from WWAP, the trip began with a tour of the controversial Venice MOSE storm surge barrier project, followed immediately by technical presentations by some of its most vocal local critics.

The students then joined researchers from the University of Padua who are exploring strategies for engaging unemployed fisherman, refugees, and others in wetland restoration and river corridor restoration projects as part of the EU’s LIFE Vimine Project. The Drexel students collected water quality samples at the inlet and outlet of a tidal wetland in the Northern Venice lagoon in an effort to quantify its potential for improving water quality.

Other excursions included to Lazzaretto Nuovo, the city’s historical quarantine, to traditional fish farms in the Po Delta region, and to one of the region’s most historical flood control districts il Consorzio di Bonifica Delta Po Adige.

The project capstone was independent research conducted by the Drexel team on how various nature-based water management strategies could be incorporated into regional climate change adaptation planning in and around Venice. This work was presented to students and researchers at the IUAV University in Venice, an institution with which Drexel has an Erasmus + agreement to promote academic exchange on climate proofing cities. Water Resource Engineering

24

Apr 2015

ROOFS ARE SPROUTING GREENERY

Dr. Montalto was recently quoted in an article on Philly.com about Philadelphia’s increasing population of green roofs and their many benefits and possibilities.

Across the city, the tops of buildings and parking lots are sprouting greenery like never before. The number of green roofs in Philadelphia has tripled since 2010, according to the Water Department, which tracks the roofs because they absorb storm-water runoff.

The city now has 111 green roofs, roughly 25 acres’ worth. An additional 64 roofs are in the queue. The completed ones range from a tiny poof of greenery atop a bus stop shelter - installed at 15th and Market Streets as an attention-getter in 2011 - to one of the latest and biggest, one-acre-plus of greenery at Cira Centre South in University City.

…

The region’s universities have not only been installing roofs, but also avidly studying them.

Among questions Drexel associate engineering professor Franco Montalto and his colleagues are pondering: Can we grow food crops, use native species (instead of desert-adapted sedum species), or create more biodiversity on green roofs in the urban Northeast? How differently do green roofs constructed on steeply sloped roofs perform? Can we adjust the design of the green roof to maximize its habitat value, such as attracting pollinators?

Read the full article at philly.com HERE >

Photo credit: DAVID SWANSON

1

Mar 2015

LESSONS ON POST-RESILIENCE

Writing from Venice, Italy, Dr. Montalto was recently featured on The Nature of Cities. He spoke on coastal resiliency, from his own experience, living in this city where dealing with flood waters (acqua alta) is a fact of life.

Walking through the flooded streets is another interesting experience. Everyone slows down—tremendously. It wasn’t initially clear to me why this was happening. Without cars, there’s always a lot of ground to cover in this city, and the average Venetian typically moves at a healthy gait. Feeling confident in my new stivali, I continued to move at this pace only to find out within a few minutes that I was suffering death by a thousand drops. It seems that each fast step kicks a few drops into the top of your boot. You don’t feel those individual drops, but keep it up and in a few minutes, your socks are soaked. I slowed down, realizing that alas, pazienza, everyone around me was used to this. When there’s acqua alta, it’s OK to be late, or to change the plan, or to cancel appointments. (Though, ironically, not for first graders. My daughter’s new teacher was careful to tell me that acqua alta is not an excuse to be late for school.) Venetians have adapted to contemporary acqua alta the way they adapted to life in a foggy lagoon over a thousand years ago. Life goes on despite it.

We are pleased to announce that

We are pleased to announce that